Bollhagen and Bauhaus - two inseparable terms

As a free-thinking and emancipated young woman, HB would probably not have stayed long at the Bauhaus. Nevertheless, she was able to internalize the Bauhaus idea early on thanks to Bogler and Burri.

Hedwig Bollhagen's understanding of form and decor

developed at a time when the Bauhaus idea prevailed among designers of all kinds: no form without function. The decor serves to highlight the form. The object should be interesting but not kitschy and remain affordable for everyone.

These principles, which she decided very early on, as well as the fortunate circumstances of working together with three great designers Bogler, Burri and Crodel, helped her to create an unmistakable signature that made her appear superior to all fashions of the time. Even today, the direct influence of the Bauhäusler can be seen in some of their designs. So she developed a fruit bowl, which Bogler designed as a model in the 1920s. HB expanded this with a sieve in the middle of the bowl and thus created a masterpiece that combines form and function with elegance and surpasses its role model.

Hedwig Bollhagen - Geschichte

Hedwig Bollhagen (1907 – 2001) lived for ceramics. Inspired by a doll dish she played with as a little girl, she was born in Hanover in 1907 and attended the technical school for ceramics in Höhr-Grenzhausen from 1925. After five semesters, the owner of the Velten-Vordamm ceramic workshop, Dr. Hermann Harkort, Hedwig Bollhagen's talent and asked her to lead the painting class. The following four years laid the foundation for Bollhagen's later work, both in terms of their technical and artistic skills. It was here that Hedwig Bollhagen developed her sure eye for form and decor, also shaped by the well-known Bauhaus masters Bogler and Burri. After the Harkort company went bankrupt in 1931, he held various positions in potteries and companies, including the Karlsruher Majolika Manufactory. Here, for the first time, elaborately handcrafted individual pieces were created, in which Hedwig Bollhagen used the sgraffito scratch technique. Finally, in 1934, she got the chance to found the "HB workshops for ceramics" in Marwitz. What followed was an unparalleled career that made Hedwig Bollhagen one of the seven most important designers in Germany.

Exhibitions and Awards:

1937 – Gold medal at the World Exhibition in Paris

1938 – Bronze medal International Crafts Exhibition Berlin

1957 – Gold Medal, Munich

1958 – Diploma of honor at the Brussels World Exhibition

1962 – gold medal in Prague

1966 – Theodor Fontane Prize

1991 – Honorary exhibition at the ANTIQUA in Berlin

1992 – Culture Prize of the district of Oberhavel

1994 – Honorary Exhibition of the State of Berlin

1996 – Order of Merit of the State of Berlin

1997 – Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

2006 – Appointment of Hedwig Bollhagen as one of the most important designers in Germany by the Goethe Institute

2008 – House of Brandenburg-Prussian History

2008 – Ceramics Museum Bürgel

2015 – Opening of the Hedwig Bollhagen Museum in Velten

2015 – Hedwig Bollhagen's estate is declared a national cultural asset

The ceramist Hedwig Bollhagen about herself

I was born in Hanover in 1907. Unfortunately, I lost my father when I was three years old. Despite the sad fate, my mother managed to give my two brothers and me a very happy childhood. We played in a beautiful old garden, where we did handicrafts, had parties and did all kinds of performances without an audience. - We were well aware that at the same time that we were allowed to play so undisturbed, the terrible war was raging, but we were still too young to really be able to appreciate the tragic events, even if we also saw the shadows cast by the war events , felt. The material deprivation, which essentially also extended to the post-war period, was actually a normal situation for us, who could hardly draw any comparisons.

Our mother had many spiritual interests and tried to encourage us to enjoy them as well. She often read to us, looked at pictures with us and showed us beautiful buildings, played music with us and tried to develop our sense of quality and teach us to distinguish the real from the false. (The word "kitsch" was part of our children's language from an early age and was a very precise concept for us.) In a post-war winter, in which coal holidays and flu holidays alternated, which of course we were not sad about, a course for some of our friends' children and for us Drawing, handicrafts and art viewing set up by the very lively potter Gertrud Kraut, who later founded Hamelin pottery. In her enthusiasm for pottery, her human kindness and open-mindedness and cheerful self-control, Gertrud Kraut is still an example and role model for me today.

At that time I had long had a special fondness for pottery, collected small doll dishes from country potteries that could be bought in nearby Hildesheim, and enthusiastically went to the so-called Pottmarkt at the Hanover Market Church, where brown Bunzlau pots and blue-painted Westerwald pots stood around in abundance . - So my first visit to Gertrud Kraut's pottery workshop in Hameln excited me a lot, and although I still had plenty of time to think about all the professions that tempted me to take up, I immediately put pottery on the "short list" and so I stayed with it. It was very difficult to get a job as an apprentice or volunteer in a pottery workshop when industry and crafts had not yet recovered from the effects of the war and the years that followed.

I found the opportunity to work for a while in a small farmer's pottery workshop in Großaimerode in Hesse and made my first attempts at turning there - with sighs that every potter will sympathize with - but was otherwise in good spirits in the profession, which was so new to me. They made pottery for village use and, in order to have a regular benefice, hand-thrown (!) ointment pots for a wholesaler who supplied pharmacies and paid only very low prices. The work was very diligent, exclusively by the family of the master potter, who did the free turning with his son and had his five daughters do all the other work. With intensive cooperation, the Kassel kiln could be fired about every three months, and the failure of the fire and the possibility of selling the goods determined the family's standard of living for the near future. If, in the master's opinion, I had tormented myself enough with turning attempts during the day, after 5 a.m. I was allowed to work on the croissant and paint plates and bowls with slip as I liked the master put together a structure from stools, boxes and boards that left nothing to be desired in terms of comfort and ingenious adaptation. Every Saturday afternoon the barber came and the master, who was very small, sat on the wheel head and, with gentle movements of the wheel back and forth, was shaved for the Sunday. On Sundays the family provided seven voices and one trumpet player for the church choir.

Friendly relatives in Kassel made me a guest student at the academy there for a few winter months. I struggled for a few weeks in the sculpture class taught by Professor Vocke, who was also trying to set up a pottery workshop. At that time he was interested in cans with metal spouts. His students were almost exclusively veterans who had either been thrown off course or had never been on the track. I believe that only a few of them used artistically, the sculptors worked in the town hall with firemen's ladders on a giant Mars, a popular theme at the time, which was related to the star that was probably just close to the earth. In our case, however, Mars was made to sit on a drum as a god, commemorating the end of the war. I wasn't allowed to take part in this mammoth work, which presented dangers, since I was the only girl in the class. So I had little opportunity to learn because I was far too dependent to try something on my own in the deserted classrooms. I took part in life drawing and art history lectures, insofar as they were not cancelled, and had time to look at the very fine Kassel collections in the gallery and museum.

After these somewhat programless weeks, which depressed me, I moved with real enthusiasm to Höhr in the Westerwald in Kannenbecker Land in 1925, where I studied at the ceramics technical school under Dr. Berdel and Dr. Bollenbach received my theoretical training. The school, which today is probably the most modern and versatile ceramics technical school in Germany, was already very good in its chemical and technical departments back then, but, in contrast to today, in the so-called "artistic" subjects such as modeling and painting so undisputed that one spent as little as possible in these really pernicious classes, some of which are taught by excellent people today. After completing five semesters at a technical school and volunteering during the holidays in a small industrial company and in Gertrud Kraut's pottery workshop in Hamelin, by the end of my technical school years I had about the knowledge that a laboratory assistant needs to bring with her as a beginner in a ceramics company.

Although I very much wanted to make crockery for everyday use, I hadn't gotten around to practicing it because, as I said, the school level in these subjects was unsatisfactory. I was fortunate to be able to work in the Velten-Vordamm stoneware factory in 1927, right after I finished my technical school. To be able to join Harkort and begin an activity that has defined all of my work to this day. Due to the intense creative joy of Dr. Harkorts, his. great love for ceramics, his unprejudiced optimism and his knowledge, the factory was certainly one of the liveliest, most varied and most interesting German ceramic companies of its time. Tableware was made from earthenware and faience, garden and building ceramics, staple goods for export and individual pieces by sculptors and painters. I owe the trust and patience of Dr. Harkorts very much, who employed me as head of the painting department, which employed 100 painting girls at the time, and as a designer, although he knew that I had not previously been trained in these things but, he hoped, was not trained either. I brought nothing to this activity, which I had not practiced in Höhr, but a great deal of enthusiasm, because I lacked any practical and human experience in the company. The volunteer times were of little consequence.

The earthenware with its rich underglaze palette and the faience technique with the beautiful softness of the brushstrokes had once again come into their own in Velten-Vordamm thanks to the indescribably talented Charlotte Hartmann. The wealth of their ideas and the really ingenious ability to take up traditional forms and decorations and bring them out with a new freshness were bound to disarm the most serious opponent of decoration. A number of artists have been inspired by Dr. Harkort: Gerhard Marks has worked on various occasions in the work with sculptures and paintings, two of his students from the Dornburg Bauhaus pottery, Theodor Bogler and the Swiss Werner Burri, worked for the factory for years, both individual pieces and series designs. Charles Crodel painted his first ceramic fireplaces and panels there, I was happy to get to know many of these creative and idiosyncratic people, to form standards for myself and to try to align myself with them. I tried to practice the painting technique of earthenware and faience production, and with the gradual habit of using the brush, I managed to create some decorations of basic geometric elements, composed of the vocabulary familiar to the painting workers. I was very interested in making utility ware that could be sold cheaply and thereby offered the buyer an opportunity to move away from the really very tasteless, mendacious ware that the china and earthenware industry was bringing to the market. I also painted one-offs, modeled, turned, and designed series molds. Some things came about that make me embarrassed when I think about them today, but I learned from everything. - Reproduction processes in decoration, e.g. Stencils and decals, for example, seriously occupied me with the consideration that these techniques have their justification, as long as a suitable form can be found that is not aimed at simulating manual work. With all the variety of decoration options, my preference for white, undecorated faience crockery grew, where the pink body shines through the white tin glaze as if through a skin. For those things that Dr. Harkort, unfortunately, the buyers didn't show much interest at the time. It was only later, when I had my own workshop, that I risked trying to produce faience-white, unpainted crockery and vessels in larger quantities, and was able to offer them with success. Since I was already very interested in the entire production process in the Velten-Vordamm stoneware factory, I also dealt with organizational work, in particular with working time studies for piecework price formation and tried to find a healthy basis in this area. determine norms. For economic reasons, the factory also had to produce staple goods for export, taking into account the wishes of customers. This could usually only be solved with compromises in an effort to find the smallest evil, for example when a tin can sleeve was sent in by a foreign customer whose peach representation was to be transferred to compote bowls, which were ordered by the thousands. When in 1931 the customs barriers that were placed around the interested countries suddenly made export impossible, the stoneware factory Velten-Vordamm, like so many other works, unfortunately had to close its doors and one of the companies that was so important in the development of ceramics as a cultural medium was lost .

Secretly harboring the desire to have my own workshop, I went on a journey to get to know as many companies as possible and to gain experience. I first worked in the majolica factory in Karlsruhe. She had a wide range of techniques and possibilities at her disposal, under the influence of Leäuger, who was not yet so distant at the time, but who had not worked directly with the manufactory for a while, and as a result there was unfortunately a lack of an active personality there, who, like Dr. Harkort, so authoritative, productive and stimulating the employees. I then worked for a short time in a Rosenthal factory in Neustadt near Coburg, where less than pleasant things were manufactured, and for a beautiful winter of skiing in Partenkirchen, in Wilhelm Kagel's workshop.

I learned to judge by good examples and even more by bad examples. The encounter with human quality and weakness in inverse proportion to goodness and defectiveness of production often amazed me. I saw the nicest people fabricate horrible things and the bad ones create the most beautiful things. I also saw bad things being created with the best means of production and good things created in primitive conditions. I spent more than half a year in a sales exhibition of handcrafted and industrially manufactured consumer goods - furniture, fabrics, jewelery and silver - which Tilly Prill-Schloemann brought to life in Berlin and several others, which was completely out of the scope of my previous work years as a separate company. The rooms with the many shop windows, directly on the zoo side and on Budapester Straße, were an exceptionally good setting for what was shown and differed strikingly from questionable arts and crafts shops. I had the opportunity to acquire material and quality feel and knowledge. It was also very amusing to observe the birth and psychology of the customer from the given perspective. I had many beautiful ceramics, e.g. B. von Leäuger, von Dreßler, Douglas-Hill, Margrit Friedländer, Lindig and others to look after and sell. Pursuing my actual goal, I soon turned back to pottery and took the first job that came my way, in Frechen near Cologne, a place where the most beautiful Rhenish stoneware was once made. Now, in gigantic salt furnaces, tubes were manufactured in all possible dimensions with a beautiful brown salt glaze. In addition, there was a sin in the production of so-called "art pottery" and devotional items, which were fired in low-firing kilns. There were all sorts of saints of all sizes and kitschy designs in large editions, which made it clear how absurd this way of producing "religious necessities" was. It cannot be overlooked that there is in fact a real need for these things in many areas, and it is undoubtedly very difficult to find good, or at least portable, forms for them. A few literary works on symbols and their signs seem to me to show such ways most closely. My work in the company was initially limited to decor designs and their application, later I became a company assistant and learned a lot about the technical context of the production process.

In my striving to be able to make pottery independently soon, I put out my feelers to find a suitable opportunity. A small, no longer operating pottery was offered for sale or lease near Berlin, which had previously made beautiful, valuable individual pieces. However, all equipment except for a muffle had already been removed. In addition, a fairly large ceramics factory, which had also been shut down for a year and used to employ around 60-80 workers, was to be sold in Marwitz near Velten, the ceramics climate that had done me so good in the past. He offered me the tempting prospect of conducting my Utility Utensils program. I didn't dare start alone, for I had learned just enough to judge what I didn't know. Knowledge of little knowledge in a varied field increases incessantly as one gains insight into it, and the advanced is more aware of it than the beginner. I was now at a crossroads and got a lot of good advice from friends and relatives not to risk such a large, demanding undertaking as Marwitz would risk, but rather to stay on a small scale. However, after much deliberation, I myself always come to the conclusion that in economically difficult times like back then, it was easier to sell mass-produced, inexpensive everyday ceramics, which I had in mind, than to find lovers of expensive individual pieces who had the money to sell them buy. Also, I didn't feel confident enough with my craft to exist in a small workshop, which might have to be started as a one-man business, since in the previous years I had mainly worked in industrial companies, where I did paint, but relatively had little time to turn.

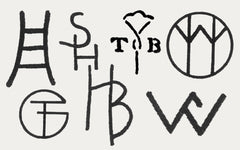

In Marwitz, there were good job opportunities for me. First, Dr. Heinrich Schild, who is an economist and craft politician in his main profession, to help me as a partner and to take over all the financial, legal and commercial functions that are necessary for the founding and continuation of such a company. Secondly, the old, experienced Velten-Vordammer works manager Wojak, who had already been in charge of the technical work in Marwitz for a while, was available. So I found the courage to start under these conditions. We called the company "HB-Werkstätten für Keramik" because I had previously called my work "HB". The Marwitz company had called itself "Hael workshops for artistic ceramics". It was essential for me that some lathe operators and several of the best earthenware and faience painters from the former Velten-Vordamm earthenware factory were willing to work in the new company.

On May 1st, 1934 I started to work in Marwitz. I first hastened to phase out from production the remaining pieces from the earlier Hael workshops collection, which I mostly disliked. I adopted some good forms because I felt it was a pity to destroy the working facilities for such things. I also revived various Velten-Vordammer decors, especially a very well-known rich pattern by Charlotte Hartmann that the painting girls still knew by heart. dr Schild enjoyed setting up and supervising the mercantile apparatus. His love for the craft, his security and his enthusiasm for development, the courage to take risks without being frivolous and his consistency created the conditions for me to be able to concentrate fully on the production.

At the Leipzig Autumn Fair in 1934, I exhibited a fairly large selection of utility forms and decorations for the first time, and with great success. It was my aim not to make fashionable hits but simple, timeless things. This effort was confirmed insofar as the majority of the models released at that time are still being manufactured today and are sold in East and West Germany. However, the development of the company and its economic consolidation proceeded more slowly than I had hoped and really required very intensive, varied work and renunciation. But there are so many sources of joy in ceramics from which one can draw strength, and exciting moments full of expectation, such as the ones that are always present at the stove, that one can never be bored and is rewarded for one's efforts. In order to be able to survive as a craft business, I did my journeyman's and later my master's examination from Marwitz. The joy of a versatile production, which I got to know in Velten-Vordamm, prompted me to ask the former employee from Velten-Vordamm, Werner Burri, who was so extraordinarily skilful, productive and very talented in drawing, for his freelance work. He created many individual pieces, all of which he shot and painted himself, but also made many designs for series production. To my great delight, Charles Crodel also agreed to collaborate. We tried all kinds of ceramic techniques together: faience and underglaze painting, gold painting, incising techniques, sculptures, stamp reliefs, plaster cuts, and tried building ceramics and garden ceramics. The rich ideas, the real artistry and the cheerful confidence with which Crodel knows how to work and convince, have caused many good architects to have Crodel's architectural ceramics designs carried out by us. There isn't a specific task that Crodel doesn't take up with interest and joy and solve artistically, provided his time permits. His ability to see intensely and to register in his head and his great knowledge create the ground on which his designs grow, which always have an intellectual content, but without being literary in the bad sense. Through Crodel I received measurements and weights to evaluate and classify. I try to use them correctly and I enjoy it. In order to create the technical apparatus and the economic conditions to be able to try out large-scale works, it was necessary to keep the ongoing series production going smoothly and to seize all opportunities for orders. In this way, some very good export connections developed, but they broke off immediately when the war began. In order to be able to maintain operations during the war, we had to adapt to prescribed manufacturing programs. We made housings for electric room heaters, tureens and dinner bowls, but we still made various individual pieces. The end of the war with the fighting and its unspeakably depressing side effects left the workshop in indescribable disorder.

But gradually the company began to "green up" a little again.

Unfortunately, circumstances meant that Dr. Schild, who had already moved to West Germany before the end of the war, could no longer take care of the business and therefore, to my great regret, resigned as a partner. Anyone who has worked in any production facility knows how difficult it was when there was a huge shortage of materials, auxiliary materials and spare parts. I've learned to stretch as far as possible and to continue working with the available possibilities. Beautiful things by Crodel have emerged again.

When it comes to building ceramics, I ventured into extensive objects and made large relief panels and building elements based on designs by Waldemar Grzimek. Here I hope to continue the experiments that have been started. It gives me pleasure to involve a few younger artists or to give them the opportunity to work with ceramics. The young Erika Manthey produced a whole series of individual pieces and also painted building ceramics in my workshop, and the very imaginative young sculptor Jürgen von Woyski occasionally tries his hand at ceramics here.

As much as I like to do work in cooperation with others that seems worthwhile to me, I hate to be seen as an "institute" that has to produce all architectural ceramic objects that correspond to its technical capacity, without having an opinion of its own to be allowed to decide on the quality of the design. In my designs for vessel shapes, I try to use ever more economical means. I try to give the "form without ornament" the honor it deserves, but I also risk trying forms that want to be enhanced and enriched by a decoration. Efforts seldom lead to success, and if one may be inclined to curse the decor per se because of all the hideous decorations of the ceramics industry and crafts, there is a demand for this kind of play by people of all times and ages of all continents in countless examples before us. The tasks posed by a relatively large workshop like mine are so diverse that one has to muster all one's strength to do them justice at least to some extent. However, the subject of making things that people enjoy should actually rule out being overly serious about the use of force. The concern to prove oneself as human beings in a circle of more than 60 employees remains the most urgent but also the most difficult. The will to put oneself in the position of one's neighbor and to feel from one's point of view makes it easier to love oneself, and this demand, in cooperation with a large circle of people, approaches everyone every day. As tempting as the vast areas of my craft are, I find it important to be aware of your own limitations within it. This need not lead to the works becoming one-sided and mannered. The risk of taking on tasks for which there is insufficient capacity in frivolous optimism inevitably leads astray. I believe that the many opportunities to till your own field avoid the temptation to take on tasks that you are not up to.

The ceramist Hedwig Bollhagen about herself.